Geometry

Zellige & Carved Stucco

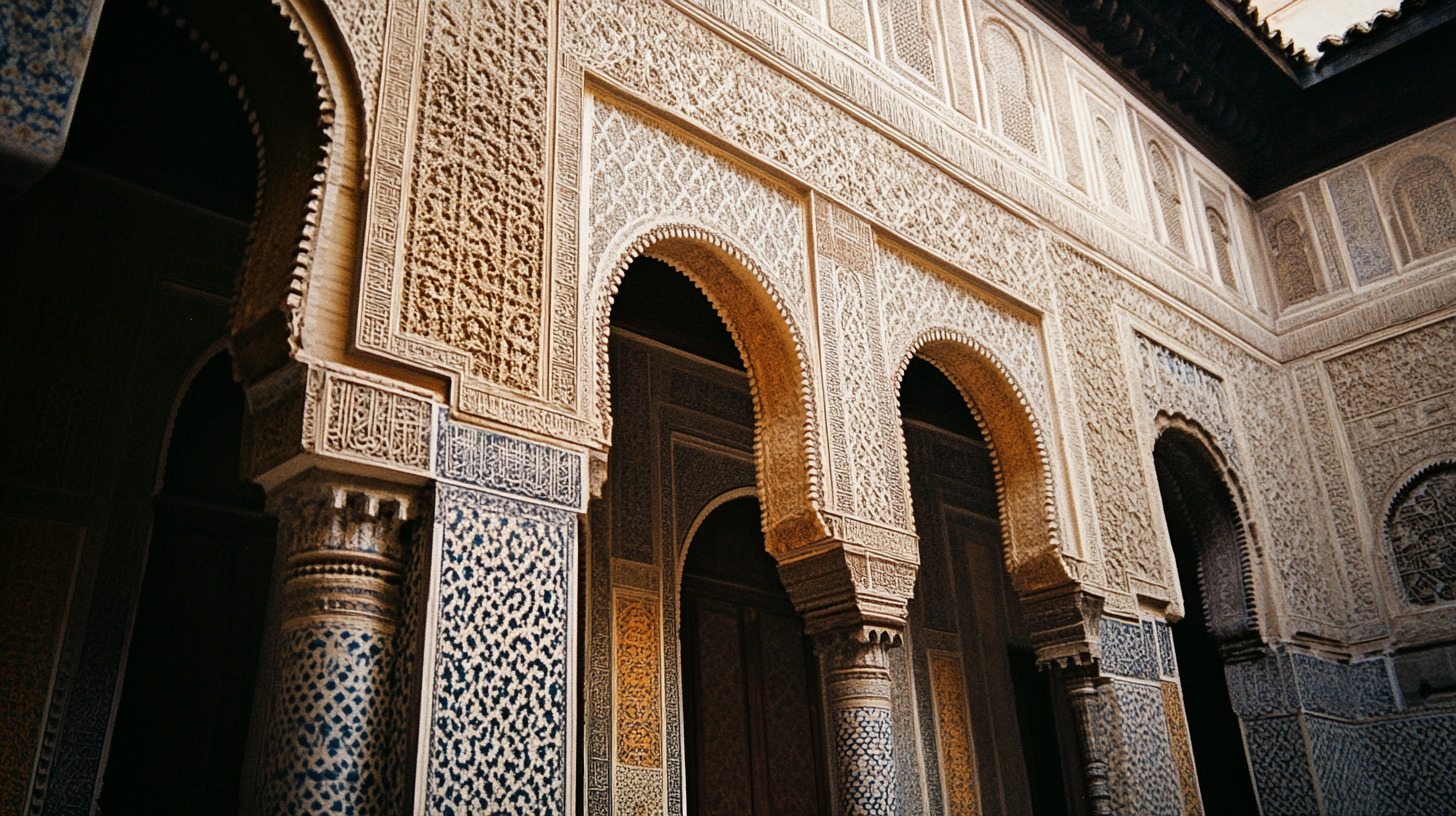

Islamic geometric art begins with the circle and a compass. From the circle, regular divisions produce grids of triangles, squares, hexagons, and stars — the raw material of pattern. In Morocco, this mathematics takes physical form in zellige: hand-cut ceramic mosaic assembled piece by piece into interlocking designs of breathtaking complexity.

The craft uses 360 named shapes in Darija. A master (maalem) works on his knees, cutting each tessera with a sharp hammer against a chisel — the same technique used since the 10th century. In 2019, Harvard's metaLAB discovered that some zellige patterns contain quasi-crystalline structures, the same aperiodic mathematics that earned Dan Shechtman the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011. Moroccan craftsmen had been laying quasi-crystals for eight centuries before Western science described them.

The second geometric medium is carved stucco (gebs). Wet plaster is incised with geometric, floral, and calligraphic patterns before it sets — a race against time that demands absolute precision. The Saadian Tombs in Marrakech represent the art's high point, with layers of carved stucco creating shadow-play as light shifts through the day.